I’ve been meaning to write this since watching Obama deliver the State of the Union last Tuesday.

Toward the end, refering to Joe Biden and John Boehner sitting behind him, he said:

…but we believe in the same dream that says this is a country where anything is possible. No matter who you are. No matter where you come from. That dream is why I can stand here before you tonight. That dream is why a working-class kid from Scranton can sit behind me. That dream is why someone who began by sweeping the floors of his father’s Cincinnati bar can preside as Speaker of the House in the greatest nation on Earth. That dream — that American Dream.

From what I know, the two of them–and Obama himself–are pretty good examples of the American Dream. They weren’t born into perfect circumstances and have still managed to become incredibly powerful in adulthood. It’s just too bad that they are the exception, not the rule. For most people, most of the time, the American Dream is out of reach.

Two things. First, lest those of us who are inspired by the Obamas, Bidens, and Boehners feel lonely, we’re not.

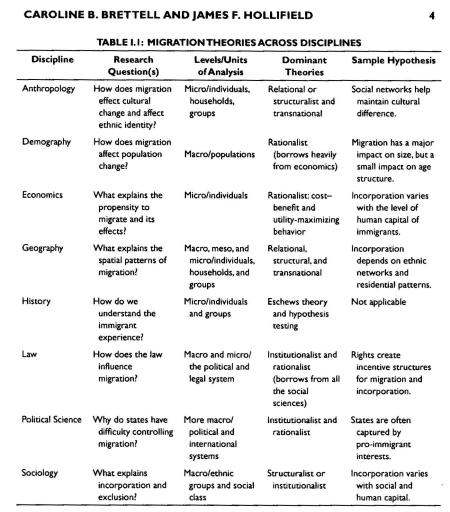

The figure below contrasts the average US perception of mobility and inequality with the average response of 27 comparison countries (from the International Social Survey Programme). Click to enlarge.

I find this data absolutely incredible. I don’t quite know what to say other than that it makes my point about the myth of mobility quite nicely. (Well, either that or Americans have managed to create a special mobility-and-equality-conducive environment that they are keeping secret from the rest of the world. I’ll get to why that’s not the case in another post.)

Secondly, this news story serves as a reminder that the structures that keep just anyone from achieving the American Dream are real.

Late last month, a mother was sentenced to 10 days in jail (she originally faced up to 10 years) for falsifying records to get her daughters into a better school.

Poe [the superintendent] said residency disputes are usually resolved after parents prove that they live in the district, pay tuition or remove their kids from the schools. This marked the first time that one of their residency challenges went before a jury in criminal court. Poe said prosecuting this case was meant to send a message.

“If you’re paying taxes on a home here… those dollars need to stay home with our students,” Poe said.

However, family and friends of Williams-Bolar call this an unfair case of selective prosecution.

I don’t know the case beyond the various news stories about it, and the NPR interview with the superintendent makes a pretty compelling case for why this situation went to court while prior cases haven’t. But if you believe education is one of the best “ways out,” it highlights one of the many structures that limit real generational mobility at a large scale.

(As an aside, one of the worst things about this story is that the mother has been working to get her teacher’s license. Now that she has a felony on her record, she probably won’t be granted licensure.)

On a slightly different note, I’ve been reading a fair amount of migration history that points to where some of the idea of the American Dream came from. And also where it went.

More on that later.

Jonas